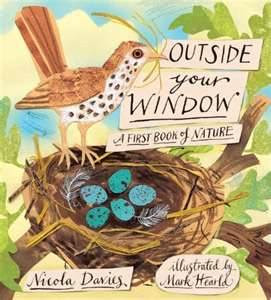

Outside

Your Window: A First Book of Nature by Nicola Davies, illustrated by Mark

Hearld (February 2012)

This

book is a case of that old expression: the whole is greater than the sum of

its parts. Though Outside Your Window is a collection of poems, it is also an

introduction to nature. Many of the lines sound like a very pleasant

science teacher explaining things such as birds, cows, and seasons. I was often

reminded of prose poetry or simply well-stated prose. But then, some of the

poems—and certainly some lines, are startlingly poetic. They are

rendered all the more so by the poetry of Hearld’s illustrations, which wrap

around Davies’ work like a quilt sewn by Mother Nature.

Be sure to take off the dust jacket. The look and design of the bare

cover are wonderful in their own right. Hearld’s artwork manages to combine a

look of 1950s children’s book illustration (e.g., Feodor Rojankovsky’s

Caldecott winner, Frog Went A-Courtin’) with nonfiction nature illustration.

The textured grandeur of his mixed-media style is made all the more

intriguing by its often-small subjects. For example, a poem called “Night” is

illustrated by a full spread that begins with yellow stalks of barley on the

left, outlined by blues in a printerly way. A brown-and-blue mouse eating

fallen grains of barley at the bottom of the page leads us across the

gutter into a dark blue night holding the white-lettered poem. A moon, a star,

and an owl overlook the right-hand page. What this description

leaves out is that the whole thing sweeps and swirls as if brushed by a night

wind. Hearld’s artwork makes the book into something positively

spellbinding—and yet the poems are ultimately science-minded. The book

is a strange and wonderful piece of art, poems and all.

I

have questioned the poetic qualities of Davies’ work. We get, for example,

lines such as these:

The

frogs are croaking in the pond

and

laying eggs like spotted jelly.

Next

week the spots will be wiggly tadpoles.

Next

month they’ll grow a pair of legs.

By

summer they’ll be tiny frogs that leap off into the world.

And

one night in another spring, when they’re big frogs, they’ll be back!

This

particular poem’s best lines frame the ones I just gave you with frog calls: “Rrrruurrrp.

Rrrrrruuurp. Rrrrrruuup.”

However,

I should note that such descriptions take on a greater meaning because of Davies’s

sharp eye for the details of nature. I had no idea that “Lambs’ tails wiggle

when they’re happy…You’ll see it happen when a lamb is feeding….” Or that

after dandelions bloom, “they fold up like furled umbrellas pointing at the

sky./Then each rolled umbrella opens/into a puff of down.” The description of a

gull’s flight is particularly fine. First the gull “runs into the wind, wings

working hard for takeoff.” Then it “scoops the air with big, long strokes….”

After soaring, the gull glides: “Now it bends [its wings] to make a W/and

slides down the wind toward the sea.” Each of the four small stanzas is

introduced with a flight sound or verb in a larger font.

Davies

often uses repetition, cumulative refrains, and other devices to give her poems

a more song-like quality. Her poem “Cherry Blossoms” ends each stanza with “blossoms”—the

word is used once in the first stanza, twice in the second, and three times at

the last. It’s a simple but true way to describe the drifts of pink that increasingly cover the

ground.

I

would have liked to see more metaphors, but when they appear they’re very good.

“Plant [seeds] in some soil,/crumbly and moist as cake mix,” for instance. At

the end of a poem called “Honey” that describes the work and sound of bees

bringing nectar, we are told that their buzz and hum is “The sound of sweetness

and the smell of flowers,/of sunny, sleepy summer—/the sound of honey.” That

last line is just perfect.

Davies

has another stupendous stanza at the end of “Tide,” but I’ll share the one at

the end of “Night,” whose illustration I talked about above. Davies describes a

night with its breeze, an owl, a star, a “moon [sailing] white and silver/in

the dark sky.” Having led us into the night, she closes with:

Sometimes

you can feel,

sometimes

you can feel,

sometimes

you can feel the world is turning.

So

yes, at first I felt that many of the poems were a bit bland. But then I began to

see this book in a different light. It really does give us eyes for looking at the

world of nature that lies outside the window. And while its voice is often

simple, it flashes powerful language every so often like streaks of lightning.

Here’s another one, where Davies extends a cliché and makes it new. Speaking of

a horse, she says:

…its

dark eye is quiet,

and

its nose is velvet,

softer

than your own cheek.

I

should mention that Davies gives us moments of humor, as in her poem “Five

Reasons to Keep Chickens.” She also gives advice, mostly of the kind that will

help children better care for the world. Sometimes it’s just nice; for instance,

she tells us we should say thank you to worms. The book ends with instructions about

how to save seeds and how to make winter cakes for birds.

Outside

Your Window grew on me like a seed sprouting up into a plant. It’s a hodgepodge,

yes, but in the best possible way—like compost (and there is a poem about

compost). Even when Davies is just chatting about nature in that kindly

teacher’s voice, there is something soothing and enlightening about her words.

Other times she really sings, and Hearld sings with her. I recommend this book

wholeheartedly.

National

Geographic Book of Animal Poetry: 200 Poems with Photographs that Squeak, Soar,

and Roar! edited by J. Patrick Lewis (September 2012)

Like

Davies’ book, this one is chockfull of poems—a poetical bang for one’s buck,

which I like very much. There have been a lot of books of animal poems over the

years (e.g., Eric Carle’s collection, Animals Animals), but some genius finally

came up with the idea of pairing photos from National Geographic’s vast

collection with an anthology of poems, in this case one created by our current

US Children’s Poet Laureate. Huzzah!

While

many of the poems are from the past, by poets such as Emily Dickinson, Robert

Frost, and Ogden Nash, more recent and current poets are also well represented.

The poems are grouped in nicely parallel sections. After a brief set of

introductory poems called “Welcome to the World,” sections proceed as follows: “The

Big Ones,” “The Little Ones,” “The Winged Ones,” “The Water Ones,” “The Strange

Ones,” “The Noisy Ones,” and “The Quiet Ones.” A section of four poems called

“Final Thought” concludes the book. The fact that there are sections about

noisy and quiet animals endeared the book to me even while I was still in the table

of contents.

While

many of the poems are from the past, by poets such as Emily Dickinson, Robert

Frost, and Ogden Nash, more recent and current poets are also well represented.

The poems are grouped in nicely parallel sections. After a brief set of

introductory poems called “Welcome to the World,” sections proceed as follows: “The

Big Ones,” “The Little Ones,” “The Winged Ones,” “The Water Ones,” “The Strange

Ones,” “The Noisy Ones,” and “The Quiet Ones.” A section of four poems called

“Final Thought” concludes the book. The fact that there are sections about

noisy and quiet animals endeared the book to me even while I was still in the table

of contents.

But

really, how do we judge a collection like this? Probably by looking at the

overall qualities of the poems and the ways in which they represent their

subjects. Variety of styles, voices, and ideas is important. Another

consideration is the fit between illustrations and text. These big picture

criteria are difficult to wrangle on a poem-by-poem basis, which leads me to

take the old-fashioned approach: going with my gut. So yes, this is a terrific

collection! But I will provide you with some examples to back that up. As is required

so often in life, let’s begin with the elephant.

The

book offers four poems about elephants on a left-hand page with a really great

photo of an elephant on the right—the photo, labeled “Asian elephant” in very

tiny letters at the lower left, shows an elephant in a pond with green hills

behind, tossing water onto his head with his trunk. The most well-known and

oft-anthologized poem on the spread is “Eletelephony” by Laura E. Richards (“Once

there was an elephant/Who tried to use the telephant—/No! No! I mean an

elephone/Who tried to use the telephone…”). The other three poems are brief: an

anonymous quatrain that has probably been around awhile comments

on the “great big trunk” that “has no lock and has no key,” but is carried

everywhere by the animal, along with two more modern poems, another quatrain and a haiku. These are the latter two:

Elephant

A

threatening cloud, plumped fat and gray,

Snorts

a thunder, rains a spray

And

billows puffs of dust away—

A

weather maker every day.

—Ann

Whitford Paul

Anthology

So

many stories

Locked

inside the amber eye

Of

one elephant

—Tracie

Vaughn Zimmer

Of

course, not every animal gets more than one poem. The variety of poems—and

animals—is just right, however. I’ll list two subjects from each section to give you an

idea: cow and orangutan, ladybug and lizard, bat and hummingbird, starfish and

walrus, armadillo and blue-footed booby, pig and raccoon, Luna moth and sloth.

As you can tell by the elephant examples, some of the poems are silly and

others are serious. Here are excerpts from two other poems, one of each type:

from

“Moray Eel”

Nighttime’s

my bright time.

It’s

head-out-and-bite time.

Give-shellfish-a-fright

time.

Swim-quick-as-a-kite

time.

Stay-out-of-my-sight

time.

Or

fins-up-and-fight time.

When

I am the blight of the sea.

—Steven

Withrow

from

“Dog”

The

sky is the belly of a large dog,

sleeping.

All

day the small gray flag of his ear

is

lowered and raised.

The

dream he dreams has no beginning.

Here

on earth we dream

a

deep-eyed dog sleeps under our stairs

and

will rise to meet us.

Dogs

curl in dark places,

nests

of rich leaves.

—

Naomi Shihab Nye

The photo that accompanies the moray eel poem is a head-on shot of

an orange-faced eel with teeth glaring and yellow eyes bulging off to the

sides. The dog photo is a bright green field of grass with a small dog’s head

sticking up out of it, mouth open in a grin and ears jutting like a

bat’s.

The best poem in the book is arguably Lewis's own, a poem so comprehensive and gorgeous that it rightfully introduces the collection. Only you might miss it if you're not careful: it's printed on the front cover beneath the dust jacket. The poem is titled "Instructions Found After the Flood," and I'll give you just the first seven lines (of 19).

Let the red fox quicken the seasons.

Let the zebra buck and clatter in the cage of his skin.

Leave the glass lagoons to the blue heron, whose eye is steady.

Let jungles whisper jaguar, whose paw is velvet.

Let the worm explore the globe, his apple.

Let the spider embroider the air.

Let tongue and belly be called reptile.

You see what I mean? This poem, like the collection, is deeply satisfying. Not

every anthology is as rich as National Geographic Book of Animal Poetry, but every public and school library

and, I hope, personal library needs this book.

No comments:

Post a Comment